Griego: Gone to Market

Returning to a city being remade — and undone — by gentrification

This past spring, I received a marketing postcard from my former real estate agent in Denver. The card was one of those oversized, glossy types advertising a listing for a Northside brick bungalow. My family and I were still living in Richmond, Virginia, barreling down on our fourth year in that beautiful, old, complicated, aspiring city. But we were preparing to move back to Colorado and trying to figure out where we were going to live.

Richmond has one-third of Denver’s population and a little less than half its land mass. It’s less wealthy as a city and is saddled with old infrastructure, narrow streets, not enough lighting, and lackluster public transportation. It is segregated in the way of all old cities because lines drawn decades ago to separate black and brown from white have hardened into walls. And walls don’t come down easy. In that, Richmond is no different from Denver.

By the time I moved there in late 2012, Richmond had begun an upswing, a beneficiary of The Resurgence of the City. All the young people with their disposable incomes and foodie inclinations and disdain for the automobile. All the empty nesters freed from suddenly too-big houses, ready to leave behind the neighborhoods where the car is still king. In that reclamation, too, of once-sagging downtowns and their satellite neighborhoods, the difference between the two state capitals is one largely of timing and scale: the Western city offers its Eastern kin a glimpse of a future in which opportunity beckons. But not for all. And always at a price.

Nine hundred thousand dollars, in this case.

That’s what the postcard says – $900,000 for the 2,000-sq. ft. brick bungalow on a corner lot on Newton Street around 37th Avenue. It is a price that is at once unbelievable and plausible because every once in a while after we moved, I would go online to check the estimated value of our old house in the same Northside neighborhood. We lived in a 1920s, two-bedroom, one-bath, galley-kitchen red brick bungalow with a little more than 900 sq. ft. upstairs and a smaller basement that was inhabitable if you weren’t picky. When the estimated market value surpassed $440,000 — $440,000! –– almost 40 percent more than our sales price, I stopped looking because my masochism has its limits.

I consider myself part of the middle-class, shrinking as it may be, and it’s a jolt to realize that I can no longer afford the neighborhood I left only a few years earlier.

I study the postcard in my kitchen in Richmond and decide to give my former Realtor some grief.

“Doug,” I say – his name is Doug Day — when his voicemail picks up. “I got your postcard on the Newton house in the mail, and I just wanted to let you know it has a typo.”

He calls back immediately. “Oh, no,” he says. “A typo. Of course, you would find a typo. What is it?”

“It says this house is $900,000,” I say.

“Oh,” he says, relief in his voice. “That’s not a typo.”

And he tells me the house is on a corner and is four times the size of a typical lot in the neighborhood. He says that’s the market in the neighborhood these days – mind-boggling. And we laugh, ha, ha, isn’t that funny/not funny.

***

Not long after that postcard made its way to Richmond, Denver officials released a report on gentrification in the city. It quantifies what your eyes tell you every time you drive through LoHi or RiNo or Five Points or Jefferson Park. Every time you see gleaming new apartment buildings towering over tidy bungalows, and block after block punctuated by the sheetrock-, glass- and metal-clad bones of Tyvek-wrapped buildings preparing to welcome the 1,000 new households moving to Denver every month.

The study, by the Office of Economic Development, focuses on “involuntary displacement,” which, depending upon how you look at it, is either gentrification by another name, or is one of its byproducts – something like revitalization run amok. Involuntary displacement most commonly refers to a working-class or lower-income neighborhood that is remade in the shape of its incoming younger, wealthier (and, typically, whiter) residents. In this remaking, longtime lower-income residents are pushed out by rising rents or property taxes.

“Involuntary” is the key word here. It separates those pushed out from those who see a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a financial windfall and cash out. The latter choose to sell their homes, and who can begrudge them? Wish them well. Pray they find a home they can afford elsewhere in a neighborhood they like. The result is the same: voluntary or involuntary, a once-neglected neighborhood takes on new life. Insiders risk becoming outsiders, shut off from the new pipeline of opportunity.

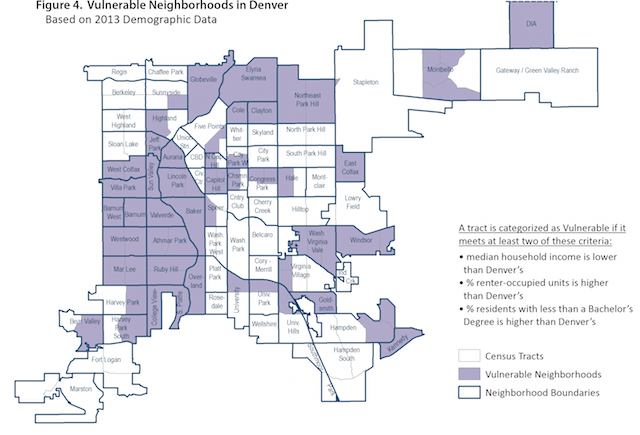

This is one of the ironies of gentrification: the neighborhoods most vulnerable to it tend to be the very same ones once hamstrung by the lack of public and private investment, by struggling schools and too few job opportunities. They are the neighborhoods with a higher than average number of renters and with lower-than-average property values, educational attainment and household incomes. The neighborhoods of the black and the brown and the working-class whites.

In the Resurgence of the City, real estate speculators saw, just as city leaders did, what was coming to these neighborhoods so conveniently close to downtown. But where the public sector plods, the private sprints. Developers, bankers, investors vault the very same walls that they once helped create. And Denver, the study points out, now ranks seventh of the 50 largest U.S. cities in terms of the extent of gentrification.

This city is now operating by an equation with three variables: housing prices, wages, and federal investment in housing. The first is rising. The second is also rising, but not nearly as quickly as the first. The third is falling. Think: a/b – c= affordable housing crisis. In this market where demand outstrips supply, a “perfect storm” has been created, the study says, which “will make it increasingly difficult for Denver’s low-and middle-class residents to stay in the city.”

Take a look at rents, as the city’s analysis does. By the end of 2014, those individuals earning the area median income of $53,700 could not afford the median rent of $1,539 for a two-bedroom, two-bath apartment. (Housing is considered affordable when it takes up no more than one-third of one’s monthly salary.) Those who earned 60 percent of the area median income – $32,220 – could not afford a median-priced one bedroom on their own – and they hadn’t been able to since 2008. And “most individuals in low-skilled occupations requiring just a high school diploma or no high school diploma could not afford to live in Denver at all,” the report says.

In this report, the city sought to identify the neighborhoods for which it is not too late to attempt a channeling of what most would agree is long-overdue investment. Call it a placing of the municipal thumb on the scale that would balance revitalization with gentrification. In these communities, the city wants to create that elusive urban ideal: the mixed-income neighborhood. It wants to extend job opportunities to those who live in neighborhoods at risk of gentrification so that wages begin to catch up with housing prices. It wants to invest in the existing small businesses. It wants to preserve and create affordable housing so that all benefit from the new shops and restaurants and services. It wants to bank land.

Westwood is one of the “vulnerable” neighborhoods. Westwood, the Westside landing pad of many of Spanish-speaking immigrants, the longtime home of working-class whites, the last neighborhood to be annexed by the city and the community that bore the brunt of the foreclosure crisis. Westwood, bisected by Morrison Road, between Federal and Sheridan boulevards, has a special place in my heart. But it has long been isolated from the rest of Denver and its housing stock is generally lousy. That it’s on the list surprises me, though it meets all the criteria: more renters, lower median household income, less educational attainment than the rest of the city. About 80 percent of its residents are Latino. It’s still possible to buy a house in the high-$100K to mid-200K range.

“It’s still an affordable neighborhood, and that’s exactly what puts it at risk,” says the area’s City Council member Paul Lopez.

Also identified as vulnerable, based upon 2013 census data: Valverde, Barnum, Athmar Park, basically all parts of the Hispanic Westside, plus the far southwestern neighborhoods home to many in Denver’s American Indian community. Globeville and Elyria-Swansea make the list, but with the move to lower the raised section of Interstate 70, that was easy to see coming. The freeway as a barrier works both ways.

“Westwood, Globeville and Elyria-Swansea, three of the poorest neighborhoods in the city are experiencing gentrification,” says Michael Miera, a community development representative with the Office of Economic Development.

Miera speaks to me not as a representative of the city, but as a Denverite, born and raised and now 63 years old. I want to know how he’s reacting to the changes he’s seeing. I hear from him the same conflict expressed by other long-timers.

“If I look at it from the perspective of just a lifelong Denver resident, I think, ‘Wow, look at my city! Look at what it’s become.’ And what it’s become, that’s a good thing,” Miera says. “Denver is one of the best cities in the country, really. I like that I can go to the Denver Center for Performing Arts. I like the sports and culture and music, the restaurants. That’s all good.

“But if I look at it from the perspective of one who cares about social justice and cares about inequities of society, then it’s sad, you know, to think that people of color, Chicanos, and Mexicanos are being driven out of the city because of this process. And that’s the big issue.

“How do the powerbrokers in the city deal with that? Do we want to be San Francisco? Do we want to be a city where no one can live unless you have a lot of money? A city that drives away business, that stops people from coming because their employees can’t live here?”

The question is not a simple matter of whether what is happening now in Denver is good or bad. It is both. The question is who defines what a city becomes. And the challenge is to find the sweet spot where public investment meets private, where government policy and market imperatives intersect and amplify opportunity in all neighborhoods, among all communities.

“That’s why we have to do what we can to achieve affordable housing in the city,” Miera says. “That’s the number one goal. Can we keep ahead of the market? I don’t know.”

****

I make another call to get a better understanding of the changes that have taken place since I left in August of 2012. This one is to Brian Eschbacher, the director of planning and enrollment services for Denver Public Schools. The public schools always have been the canary in the coal mine. I want know what he’s been seeing.

He starts with the number of homeless students. According to district data, DPS counted 2,519 homeless students last school year – up every year since 2010 when 1,515 homeless students were counted. Most of them are not in-the-streets homeless. A higher percentage than ever, 58 percent, are doubling up, living with other families, a phenomenon the district ties directly to the lack of affordable housing, including long waits for subsidized housing, in the city.

“If your landlord sells your place and you used to rent for $600 a month and now you can’t find anything, you are forced to find a place to live with someone else,” Eschbacher says.

The changes impact both students – those forced to move and the friends they leave behind – and the school system, which is seeing a drop in the number of its lower-income students. For every percentage point drop in the number of students eligible for free-or reduced-price lunch, Eschbacher says, the district loses $1 million to $1.5 million in federal funding. The number of such students has dropped four percentage points in the last two years and is projected to decrease another 8 to 10 percent in the next four years, through 2020, he says.

This is coming on top of a projected decline in general enrollment simply because as housing prices increase, the number of families with public-school age children falls. “If you take a $100,000 home and scrape it to build $400,000 condos, it’s less likely that we will get students,” Eschbacher says. “Our student population grew so, so fast and now we have dramatically slowed our growth. It’s shocking to have it happen so quick.”

I ask him where the families are going. The first moves seem to be within Denver, he says, from northwest Denver to southwest Denver, from North Park Hill to Montbello. Student transcripts tell the district that much. But after that, he said, it appears as though families are moving north to Adams County, to Commerce City.

“You have a metro area shifting,” he says, “and it’s really out of the city.”

***

Which is where we end up. My family and I return to Colorado at the end of July. The changes in Denver in such a short time astonish me. The freeways are laden with the kind of traffic that reminds me of my years in Southern California. The beloved neighborhood bowling alley where we took our kids on Sundays has become a Natural Grocers. A friend tells me the longtime manager, a native Westsider who knew everyone, is now working at Target. Chuck’s Barbershop is still there, but Chuck Floyd, who bought the place in 1953, just sold it to another barber. A pawn shop at the mouth of tiny Edgewater, which somehow always felt to me like an untamed outpost in the middle of a metropolis, has been replaced by a brewery. A lease on a 534-square foot. one-bath studio at the new luxury Alexan Sloan’s Lake apartments starts at $1,390.

My sister, who lives in Centennial, drives me to Denver’s RiNo for dinner. We pass through the fast-growing canyons of brick and glass into the warehouse district that is a warehouse district no longer but a hip urban-artisan village-in-the-making. She takes me to a 19th-Century brick foundry turned supercool mercado, with food and drink and charming little markets that sell flowers and wine and bread and beer and cheese. Online it is described as a “one-stop shopping experience for the food-obsessed.” The place is fantastic. The change astounding.

We have decided to live in Fort Collins. It wasn’t much of decision, actually. Denver is too expensive and my husband is joining the faculty at CSU. Someone tells him that if everyone in the country wants to live in Denver, then everyone in Denver wants to live in Fort Collins. Perhaps that it is true because the house hunt is brutal. As in Denver, homes for sale are getting multiple bids. Multiple not as in three. Multiple as in 8, 9, 10. Would-be buyers are waiving inspections and appraisals. They are paying cash.

I joke that I am moving through the stages of house-hunting grief: Disbelief, disappointment, anger, resentment. Full of indignation, we say screw it, and decide to wait for the cooler seasonal markets of late summer and fall. We manage to find an overpriced three-bedroom apartment a mile from the kids’ school.

Everyone wants to talk about how much has changed here since we left. The rising home values are good news for my friends, many of whom, like us, could be said to have been among an early wave of gentrifiers. Their homes have skyrocketed in value. But the changes are also a source of sorrow for the long-timers who see in the scrape-offs disrespect for the history of a place, for the communities that sheltered the Italian, Mexican, black and white families and the workers who helped build this city.

Perhaps this is the predictable lament of one generation watching the reshaping of its legacy by another. Perhaps Denver is being remade in some way that fundamentally alters its identity.

The summer housing market cools from a boil to a simmer and we resume our search, finally finding a patio home at a price we can afford. It’s smaller than our home in Richmond with an unfinished basement. But it is lovely, and in the same school zone as our apartment. The mortgage is $500 less a month that what we are paying in rent.

We await the bank’s appraisal and count ourselves lucky.

Photos by Allen Tian, The Colorado Independent

![]()

Comments

Griego: Gone to Market — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>